The effects of landscape heterogeneity on disease dynamics

What is it and why do we care?

Increasing the connectivity of a landscape (e.g., increasing the ability of a host to move between habitat patches) can have unexpected effects on pathogen spread. For example, while we might expect that increasing habitat connectivity increases pathogen spread, interactions between host dispersal behavior and the suitability of habitat patches for pathogen persistence can lead to situations where increasing landscape connectivity decreases pathogen spread and persistence. Moreover, the effects of landscape connectivity on pathogen dynamics are further complicated by variability in host communities among habitat patches (i.e., species-level heterogeneity) and variability among individuals within a species (e.g., individual heterogeneity in pathogen intensity or movement behavior, ). We currently lack a framework in disease ecology that i) incorporates individual, species, and landscape heterogeneity and ii) can be parameterized with commonly-collected data. Such a framework would allow us to ask questions of applied relevance, such as: “What are the relative contributions of particular individuals, species, and habitat patches to transmission risk?”

What are we working on?

A key goal of our research is to promote a data-driven understanding how heterogeneity at the individual, species, and landscape level interact to affect pathogen dynamics. There is unlikely to be a one-size-fits all framework that integrates across scales of heterogeneity as this framework will depend on the ecology of the host-parasite interaction of interest as well as the available data.

Metacommunity models of amphibian pathogens

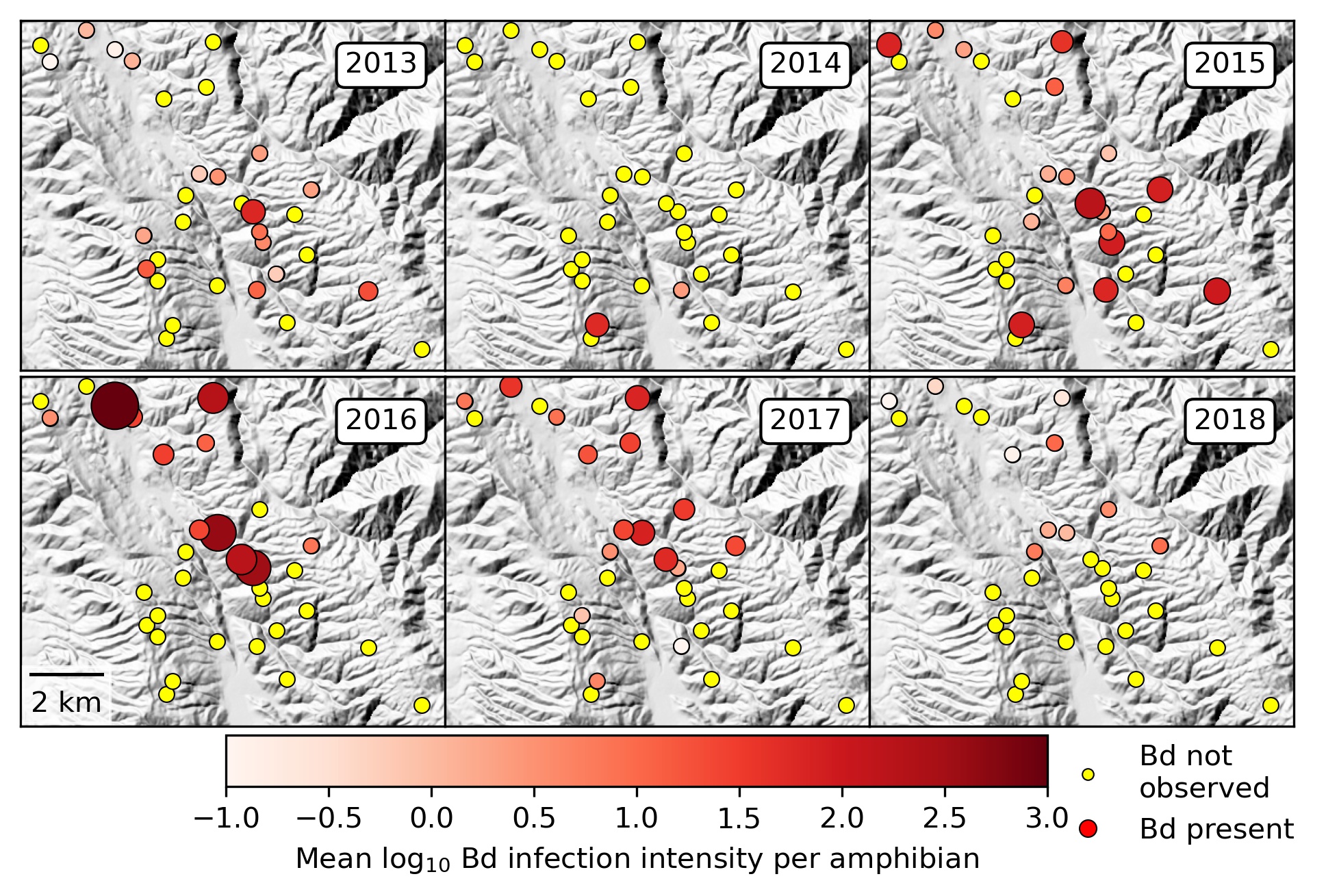

A fundamental goal of disease ecology is to predict when, where, and why disease outbreaks occur. Despite recent progress in our ability to forecast the dynamics of host-specialist parasites (e.g., measles, cholera, influenza), we know considerably less about multi-host pathogens that are nested within complex ecological communities, which includes most emerging infections of humans and wildlife. Many such infections exhibit dramatic heterogeneity among host individuals (e.g., superspreaders), host species (e.g., reservoir hosts), and habitat patches (e.g., transmission foci), frequently leading to the occurrence of infection “hotspots” in space or time that disproportionately affect disease dynamics.

Yet isolating how heterogeneities across biological scales interact to determine the distribution of hotspots has been hindered both by the absence of a mechanistic framework and a shortage of sufficiently replicated spatiotemporal datasets on host-parasite interactions, limiting opportunities for proactive disease management. Our research combines extensive spatiotemporal datasets with recent advances in metacommunity theory and disease ecology to predict how hierarchical levels of biological organization, including species, communities, and landscapes, interactively contribute to disease emergence in amphibian communities, and ecological communities more generally.

Yet isolating how heterogeneities across biological scales interact to determine the distribution of hotspots has been hindered both by the absence of a mechanistic framework and a shortage of sufficiently replicated spatiotemporal datasets on host-parasite interactions, limiting opportunities for proactive disease management. Our research combines extensive spatiotemporal datasets with recent advances in metacommunity theory and disease ecology to predict how hierarchical levels of biological organization, including species, communities, and landscapes, interactively contribute to disease emergence in amphibian communities, and ecological communities more generally.

Here is some of our recent work on the topic: Wilber et al. 2021, Ecology Letters, Wilber et al. 2021, Journal of Animal Ecology

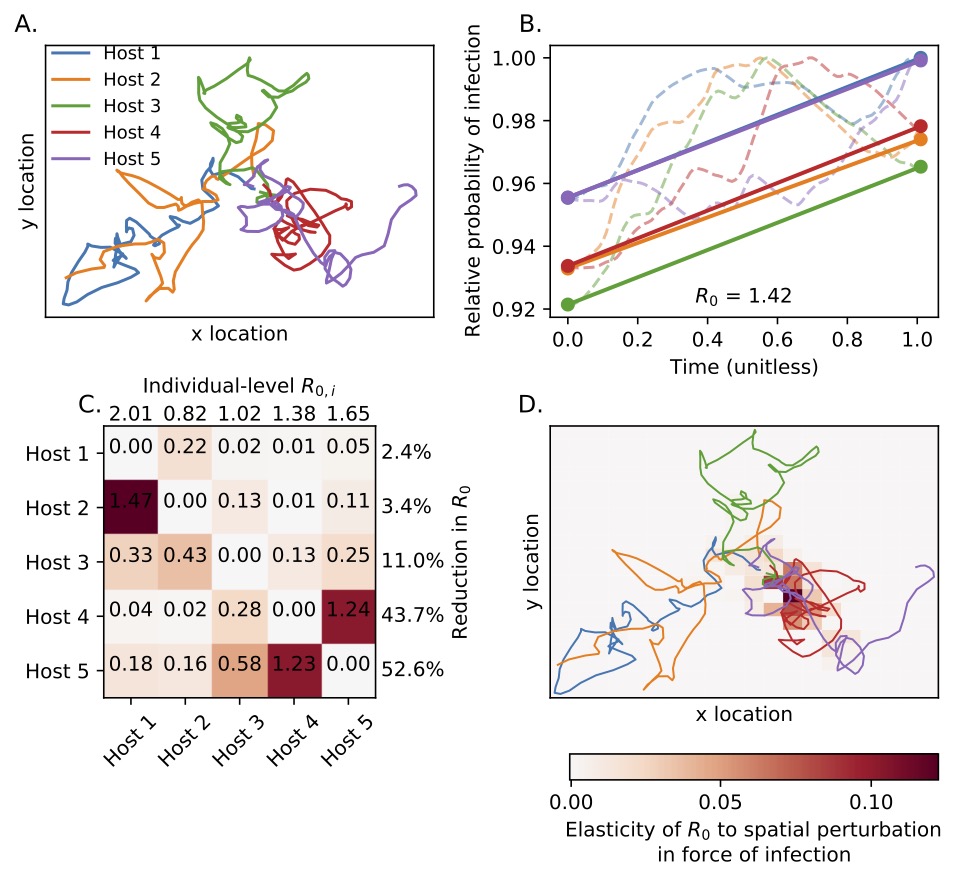

From animal movement to pathogen invasion on the landscape

We are currently developing a framework known as “movement-based modeling of spatiotemporal infection risk” (MoveSTIR). The goal of MoveSTIR is to provide a flexible framework to link empirical movements of animals on landscapes to potential disease risk. At a minimum, MoveSTIR takes in empirically observed movement trajectories and basic information about a pathogen of interest (e.g., average persistence time in the environment) and outputs individual, spatial, and temporal maps of potential infection risk. We envision this framework being able to answer both applied questions such as,

- Based on observed movements, which animals pose the greatest risk for pathogen invasion?

- How do observed animal movements translate to hotspots on the landscape? Are these hotspots predictable based on characteristics of the environment?

- For pathogens that can persist in the environment, what is the relative contribution of direct transmission and indirect transmission to infection risk?

and theoretical questions such as

- How does asymmetry between individuals in infection risk lead to spatial bottlenecks in pathogen invasion?

- How does transmission scale with density in empirically-observed, dynamic contact networks?

We are currently using this framework to understand the spatial and temporal drivers pathogen transmission in various ungulate diseases.